It’s a brave move to upend your entire family to seek a fresh start – or safety – in a new country: even braver when the country you’re moving to has a completely different language, structure and cultural outlook.

For the children of migrant and refugee families, it can be especially tough – not only trying to fit into a completely new environment but, as the fastest learners in the family, often speaking for older relatives who struggle to navigate everyday tasks and to understand local rules, regulations and ways of doing things.

Coupled with the challenges of getting kids into schools, parents into jobs and keeping a roof over everyone’s heads, it can be a highly vulnerable time for families – especially those who have come from conflict zones or have had little previous access to education.

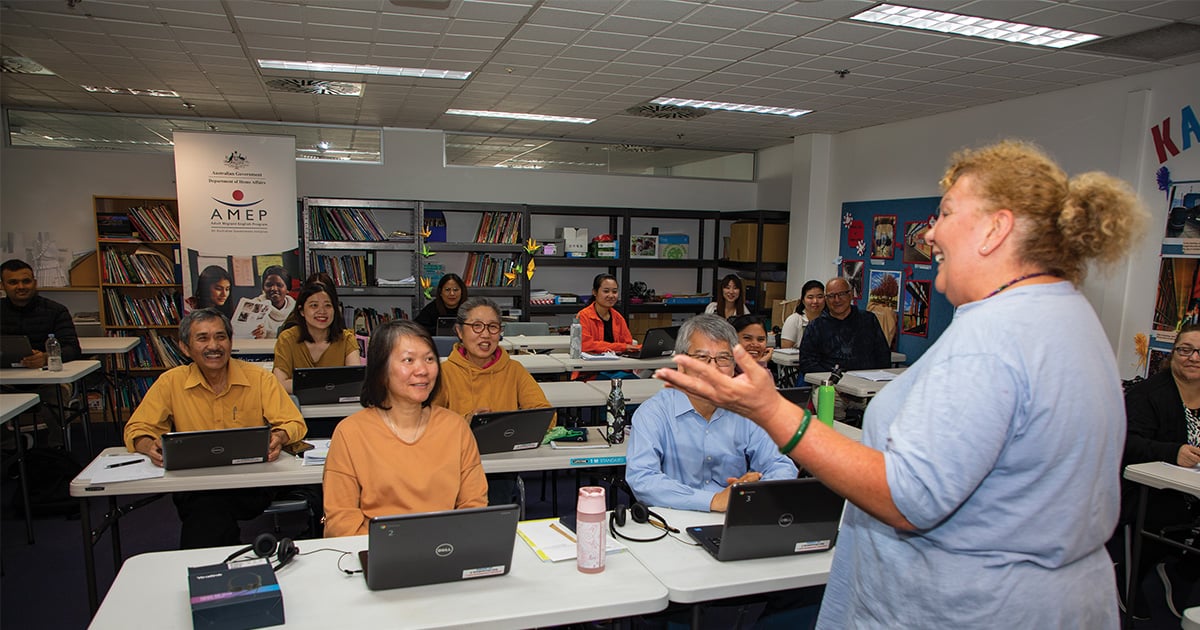

For decades, the Federal Government has sought to ease the transition by providing an immersive settlement program that not only helps new migrants and humanitarian entrants improve their English skills, but supports them to acclimatise socially, tackle daily activities, and navigate health, education, social security and other government and service systems.

The Adult English Migrant Program (AMEP) was originally established in 1948 to help thousands of refugees displaced by World War II develop English skills and settle into Australian society.

In the decades since, the AMEP has directly helped more than two million migrants and humanitarian entrants, in turn delivering a range of positive impacts for their children and families.

Until recently there’s been no way to measure the extent of that impact, but now an exhaustive evaluation led by a team from The Kids Research Institute Australia has used the power of data linkage to show just how valuable the program is.

Last year, a team of researchers led by Professor Francis Mitrou and Dr Ha Nguyen completed the AMEP Impact Evaluation Project – the most comprehensive study of AMEP participation undertaken in the $300 million per year program’s 76-year history.

Working closely with the Department of Home Affairs, the team spent four years building a profile of those using the AMEP, analysing its effectiveness, and evaluating its economic and societal impact beyond simply improving migrants’ English. Across five research papers, they examined outcomes including language, employment and income.

The research found AMEP participation improved clients’ English proficiency, especially when they studied for longer periods, and was associated with improved labour force participation, higher income levels, and reduced reliance on income support. But Professor Mitrou said that while understanding these kinds of outcomes had been an important objective, they were only part of a much bigger impact story.

“When we consider people from non-English-speaking backgrounds – particularly humanitarian refugees or people who may have had very little access to education and who arrive in Australia with nothing – the AMEP is a game-changer in terms of how we set those families up for success in Australia,” he said.

“It’s a powerful tool that helps lift disadvantaged migrant families out of poverty and isolation. That in turn has powerful consequences for their children’s wellbeing, education and ability to thrive and lead the happy, healthy lives we want for all Australian kids.”

More than just words, AMEP embeds families in the Australian way of life

While the AMEP’s key aim is to improve migrants’ English, communication and digital skills to help them into employment or further studies, there is also a strong focus on social skills and community connection.

“We want them to be able to feed their families and pay their rent and to get them off the social system as much as possible, but it’s also about building up their social skills and confidence,” said Rania Soliman, who leads AMEP delivery across North Metropolitan TAFE’s sites.

“When people arrive in Australia they have no clue about how things work or the social aspects of our society, so we build those topics into the program as well.”

This could be as basic as water safety: with some migrant families never having seen beaches or pools before, it’s vital to teach them how to keep themselves and their children safe.

“Schooling is another aspect – they don’t know a lot about how the Australian schooling system works so we support them in that,” Ms Soliman said. “We also make them aware of community-based things such as sports they can do for the kids and themselves.”

With women making up 65 per cent of AMEP participants, a key ingredient in the program’s success has been on-site, free childcare. PJ O’Keefe, who manages the AMEP portfolio for South Metropolitan TAFE, said onsite creches had made the AMEP vastly more accessible for female clients, many of whom were juggling significant family and cultural responsibilities.

“Being able to bring their kids with them opens up their opportunity to participate,” he said. “If we didn’t have this, so many people would be locked out of learning and development and the ability to participate socially and economically in Australian life.

“That learning doesn’t just benefit them as individuals – they’re developing skills that benefit the family group and their community.”