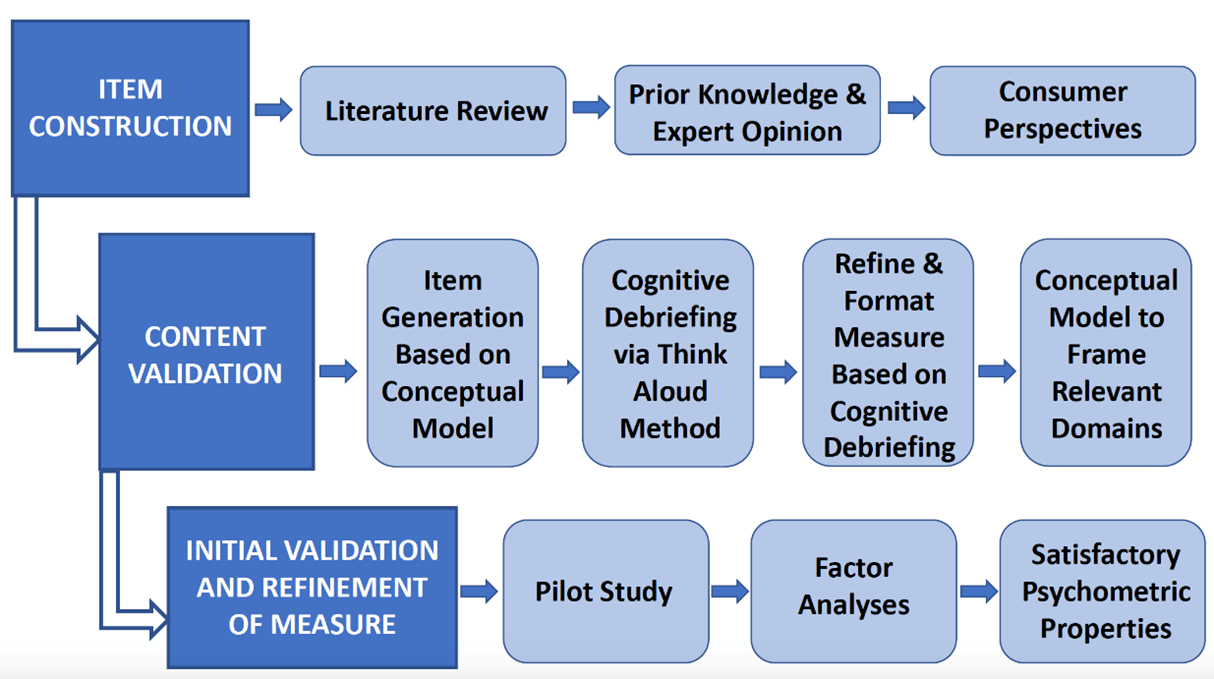

QI-Disability was designed by Australian researchers in direct collaboration with the families and carers of individuals across the spectrum of intellectual disability. This section presents a figure showing a summary of the methodologies for developing QI-Disability and a narrative describing the research we have conducted using QI-Disability.

Development Process

We undertook four qualitative studies to investigate the domains of quality of life (QOL) important to children with intellectual disability. In-depth interviews were conducted with parents of five to 18-year-old children with either Down syndrome (n=17), Rett syndrome (n=21; a severe genetic neurodevelopmental disorder mainly affecting females), cerebral palsy (n=18) or ASD (n=21).3-6 Together these conditions represented a range of characteristics seen in the broader population of those with intellectual disability including functional, behaviour and socialization difficulties; medical comorbidities; and different needs for autonomy. QOL domains were consistent across the four groups and included physical health and emotional wellbeing; pleasure in communication, movement, and day-to-day routines; and satisfaction derived from social connectedness, leisure activities and the natural environment. These data were consistent conceptually with the ICF.7 We found subsequently that the 6 domains of QOL were consistent for children with the CDKL5 deficiency disorder8 and for adults with Rett syndrome9 and the CDKL5 deficiency disorder.8

Content validation

Questionnaire items were extracted from the 77 parent caregiver interview data. A draft of QI-Disability was administered to 16 parent caregivers with a child with intellectual disability. Parents participated in a cognitive interviewing procedure known as the “think-aloud” method. After reviewing all think-aloud interview data, 41 of the 50 items remained in the draft measure: six of the original items were excluded because they did not capture the intended meaning of the item, and three items were combined with other closely related items to avoid repetition. The wording of 24 (48%) items was revised to align with parent interpretations. This development process provided evidence for the content validity of QI-Disability because ongoing consumer feedback shaped the extraction of items from the qualitative dataset.10

Psychometric validation

Initial validation:

QI-Disability was administered to 253 primary caregivers of children (aged 5-18 years) with intellectual disability across four diagnostic groups: Rett syndrome, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, or autism spectrum disorder.11

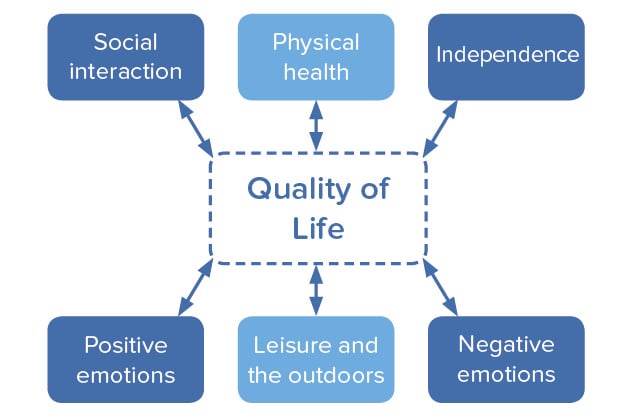

- Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses: Six domains were identified: physical health, positive emotions, negative emotions, social interaction, leisure and the outdoors, and independence.

- Goodness of fit of the factor structure: Goodness of fit statistics were satisfactory and similar for the whole sample and when the sample was split by ability to walk or talk. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.72 for “physical health” to 0.90 for “positive emotions”.

- Comparison of diagnostic groups: On 100-point scales and compared to Rett syndrome, children with Down syndrome had higher leisure and the outdoors (coefficient 10.6, 95%CI 3.4,17.8) and independence (coefficient 29.7, 95%CI 22.9, 36.5) scores whereas children with autism spectrum disorder had lower social interaction scores (coefficient -12.8, 95%CI -19.3, -6.4). Scores for positive emotions (coefficient -6.1, 95%CI -10.7, -1.6) and leisure and the outdoors (coefficient 5.4, 95%CI -10.6, -0.1) were lower for adolescents compared with children.

Test–retest reliability and responsiveness:

QI-Disability was administered twice over a one-month period to a sample of 55 primary caregivers of children (aged 5-19) with intellectual disability. Caregivers also reported their child’s physical and mental health and completed a four-item Perceived Stress Scale to assess parental stress.12

- After accounting for changes in child health and parental stress, adjusted ICC values showed substantial agreement for the total QI-Disability score and four domain scores (adjusted ICC≥0.80). Adjusted ICC scores indicated moderate agreement for the Physical Health domain (adjusted ICC=0.68) and fair agreement for the Positive Emotions domain (adjusted ICC=0.58).

- The minimal detectable difference for the total score was 4.83 out of 100, indicating the change that is greater than within subject variability.

- Improvements in a child’s physical health rating were associated with higher total, Physical Health and Positive Emotion domain scores, while improvements in mental health were associated with higher total and Negative Emotions domain scores indicating better quality of life. This indicates satisfactory test-retest reliability and preliminary evidence of its responsiveness to changes in child health.12

Known groups validation:

The predictors of QOL have been investigated in three studies. Findings are consistent with theory and provide further evidence of the validation of QI-Disability.

- Children who are fully dependent on others for their personal needs and those who find it difficult to make eye contact when speaking have lower QOL scores. More frequent participation in the community was associated with higher QOL scores, irrespective of the level of functional ability.13

- Comorbidities also influence the child’s QOL, particularly the presence of recurrent pain, insomnia and excessive daytime somnolence are associated with poor QOL scores.14

- Rett syndrome - Children with the Arg294* mutation had low QOL scores, driven by difficulties with sleep and behaviour.15

We have developed guidelines for how to manage missing data.2 We have reported the parent psychological distress does not have a mediating or moderating effect on the relationship between functional abilities and QOL as measured by QI-Disability.16 We have used QI-Disability in analyses for the CDKL5 deficiency disorder.17-20 The domain framework has informed interpretation of psychometric evaluation of qualitative data on child experiences following gastrostomy,21 the EQ-5D-Y when used for children with intellectual disability22,23 and meaningful change in SCN2A-DEE.24 See the reference list below.